My family moved to Modesto, California in 1984, a few weeks before I started first grade. Our rental home backed up to empty, weed-covered fields on the edge of town, which my new friend Kime and I loved to explore. We rode our dirt bikes and dug for buried treasure, unbothered by the lack of shade and consistently sweltering heat. Two years later, when my mom and I moved into a new home, the edge of town had already moved outward at least a mile. Five years later, when I returned for a visit, newly built houses bulged even further into the surrounding orchards and farmland, placing even more distance between our first California home and the nearest vacant lot for a child to dig and play in. Development was booming, and it transformed Modesto nearly overnight.

It is no secret that Minnesota’s Twin Cities region is growing steadily larger, just like my childhood home in California. According to demographic data and projections from the Metropolitan Council, the seven county metro will add an estimated 350,000 residents in the next twenty years, growing from 3.2 million people to more than 3.5 million. Exurban communities just outside the urban core are growing rapidly as well.

Washington and Anoka Counties are two of the top ten fastest growing counties in Minnesota, and Isanti is close behind at number eleven. There was a 28% increase in property values in northern Washington County in 2022, and, according to the Star Tribune, the cities of Lake Elmo (1), Lindstrom (2), Cambridge (5), and Stillwater (9) are among the hottest housing markets in the state. Growth helps to support local businesses, fund public services, and keep our communities vibrant, but all those new houses have to go somewhere.

What tools exist to help small towns grow in a way that protects natural resources and maintains a sense of community?

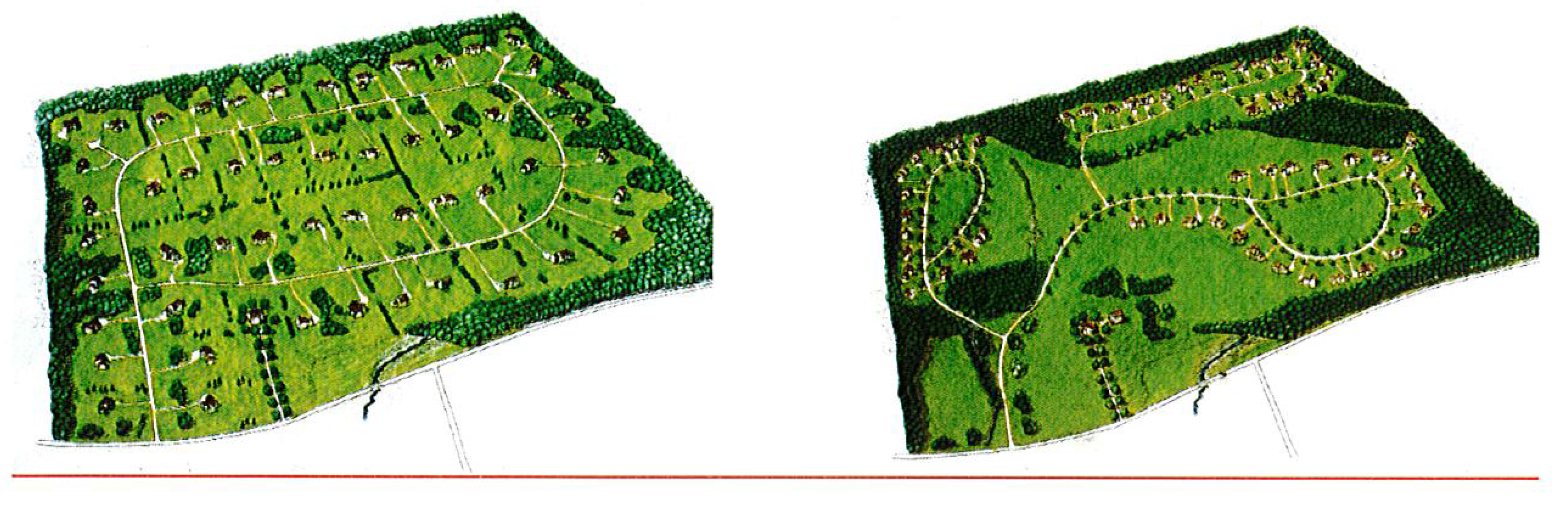

Conservation development (sometimes called cluster design) is one strategy that can be used to preserve open space and reduce infrastructure costs when new neighborhoods are platted. The idea is to group homes closer together on smaller lots, so that prairies, woodlands, and other natural areas can be permanently protected. If we consider a theoretical example of a 50-acre parcel platted for residential development, it is easy to see the benefits of conservation design.

One option for our theoretical neighborhood would be to divide the available land into 5-acre lots and build one home on each. In this example, each homeowner would get a nice large lot, but we would also end up with a lot of habitat fragmentation caused by roads and driveways. At the city or township level, this approach to development is expensive to maintain across a large area, puts a strain on emergency services, and usually leads to either higher taxes or minimal long-term maintenance.

If we applied a conservation design approach to our theoretical example, we could cluster ten new homes on ten acres of land and then set aside the remaining 40 acres in a permanent conservation easement to be managed as natural prairie, woods, or wetlands. This design could also be adapted to include a mix of single-family and multi-family units to increase the total number of homes built and provide more affordable options. The conservation development approach better protects natural resources and could be 12-20% cheaper to build, due to cost savings on infrastructure such as water, sewer, and roads.

Local examples of conservation design neighborhoods in Washington County include Wildflower, Fields of St. Croix, and Cloverdale Farms neighborhoods in Lake Elmo, Inspiration in Bayport, and Jackson Meadows in Marine on St. Croix.

Another tool for growing communities are Minimal Impact Design Standards (MIDS), which help to minimize the impact of development and redevelopment projects on water resources. MIDS performance standards require developers to manage and treat runoff from small rainstorms (1.1 inches or less) on site in order to minimize flooding, reduce stormwater runoff pollution to lakes, rivers, streams and wetlands, and protect groundwater aquifers. MIDS standards can be applied to traditional residential and commercial development projects, as well as linear projects like roads and trails.

Local communities that have adopted MIDS performance goals for stormwater management include Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District, Rice Creek Watershed Districts, and Valley Branch Watershed District, as well as the communities of Bayport, Baytown Township, Lakeland Shores, Lakeland, Lake St. Croix Beach, Lindstrom, Oak Park Heights, St. Mary’s Point, West Lakeland Township, and Woodbury.

Within the Lower St. Croix Watershed (Minnesota side only) funding is available to help cities and townships review and update ordinances to incorporate MIDS, adopt innovative shoreland standards, and utilize conservation design strategies to protect natural resources during development. Find more information at www.lsc1w1p.org/for-communities.

Great information!Sent from my GalaxyAllison McginnisBird City Stillwater/SSMN, lead coordinator 651 206 6207

LikeLike