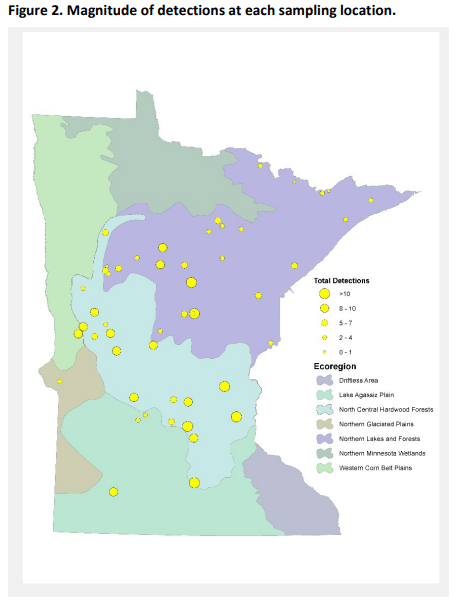

In 2017, researchers from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) made a shocking discovery. Fifty out of fifty lakes tested in a statewide random-selection study contained at least one chemical derived from pharmaceuticals or personal care products.

The most commonly found chemical was the hormone estrone (70% of tested lakes), followed by the insect repellent DEET (76% of tested lakes in 2011 and 50% in 2017). Other chemicals, including cocaine, antidepressants, oxycodone, and veterinary antibiotics were detected in numerous lakes as well. In fact, of the 163 chemicals tested by the MPCA, 55 were found in at least one lake. (See: Pharmaceuticals and chemicals of concern in Minnesota lakes, MPCA, 2021)

How are all of these chemicals ending up in our water?

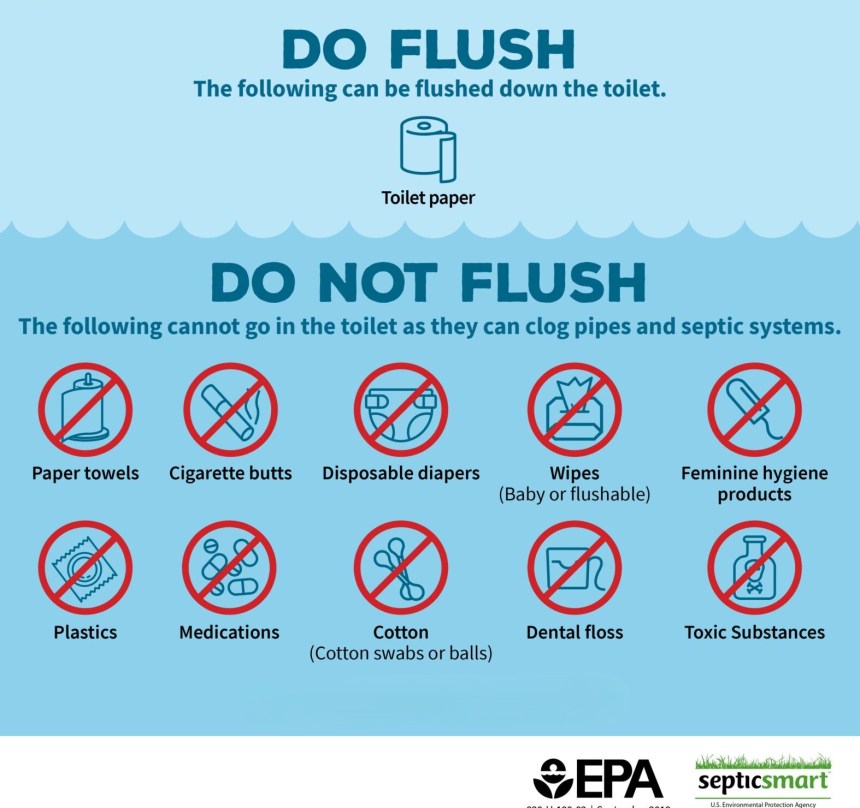

When people dispose of old and unused medications down a sink or toilet, it is highly likely that at least some of those chemicals will end up in a lake or river. This remains true whether you’re connected to city sewer or out in the country on a private system.

In the Twin Cities metro area, 1.8 million homes that are connected to city sewer send their wastewater to the Metro Facility in St. Paul, which is operated by the Metropolitan Council. After treatment, the water is released to the Mississippi River. Elsewhere in Minnesota, your wastewater could be sent to Lake Superior, the Minnesota or St. Croix River, or another nearby water body. Though there have been many advances in wastewater treatment over the past 100 years, these systems are designed to remove conventional pollutants like phosphorus, bacteria, and organic matter, not the complex and stable chemical structures found in pharmaceuticals. As a result, only about half of all prescription drugs arriving at these plants are removed by the wastewater treatment process.

Private septic systems are similarly ill-equipped to remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater. These chemicals are designed to be stable and non-biodegradable, making them difficult to break down in conventional treatment processes. Additionally, septic tanks rely on beneficial bacteria to break down waste. Antibiotics and other drugs can actually kill these microbes. So, if you dispose of household medications down the sink or toilet, you could actually end up wrecking your system.

Intuitively, it is obvious that we shouldn’t find cocaine and antidepressants in our lakes. But, even some of the more mundane chemicals can act as endocrine disruptors that affect the growth and development of fish and amphibians.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has conducted numerous studies on the rate of intersex fish in major river systems around the U.S. and found the issue to be pervasive. As an example, 73% of the smallmouth bass tested in the Mississippi River near Lake City, Minnesota during a 2009 study had characteristics of both sexes. In other research, Dr. Heiko Schoenfuss at St. Cloud State University has documented impacts from endocrine disruption in fish, even when there are very low concentrations of chemicals in the water.

The best and easiest way that you can help to prevent pharmaceuticals from ending up in our water is to take your old and unused medication to a county drop-box. These drop-off sites are free and anonymous and accept pills, blister packs, creams and gels, inhalers, patches, liquids, powders and sprays. Find a location near you in Minnesota. East metro counties are listed below:

In addition, many counties also operate household hazardous waste facilities where you can dispose of a wide range of household hazardous materials, recyclables, and waste.

In Washington County, the North and South Environmental Service Centers accept hazardous materials, household chemicals, electronics, sharps (needles, syringes, and thermometers), vaping devices, plastic bags and signs, scrap aluminum and steel, recycling, and food scraps.

Links to other county environmental centers are listed below: